By Sikivu Hutchinson

Driving L.A.’s cesspit 405 freeway one afternoon in

the late eighties, a voice on the radio punched out at me like a bolt from the blue.

It was high-pitched and commanding, testifying to “dirty laundry” truths on

sexism, victim-shaming, and Black patriarchy that Black women weren’t “supposed”

to speak in public. It was a voice that calmly gave no quarter, straight up,

with the lilt of a schoolroom griot.

Discovering bell hooks’ work and voice in the twilight of the terrorist Reagan-Bush regime was a revelation. She trafficked in irreverent, daring, give no fucks language that was alternately tender and nurturing, swaggering and pugilistic. Her devotion to writing as radical resistance rocked my then twentysomething self, scribbling half-aborted stories in grubby journals; always insecure about their worth, always weathering rejection after rejection by white (and, sometimes, Black) gatekeepers, always pissing deep into the void of self-doubt and debt.

hooks’ dogged championing of Black women’s writerly self-determination in the midst of caregiving and self-sacrifice was one of many unapologetically Black feminist middle fingers she gave to respectability politics. The first pages of her 1989 book Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black explore her ambivalence about being raised in a working class Southern Black family where her voracious literary interests, skepticism, and poker in the eye questioning were a source of pride and tension. Coming to voice, she reflects on how young Black girls were not recognized as rightful heirs to Black charismatic oral traditions dominated by men. As a child growing up in rural Kentucky, she reveled in women’s talk, for, it was in “this world of loud talk, angry words, women with tongues quick and sharp…touching our world with their words, that I made speech my birthright — and the right to voice, to authorship, a privilege I would not be denied. It was in that world and because of it that I came to dream of writing.” In these highly gendered spaces of Black verbal performance, “punishments for (certain) acts of speech seemed endless. They were intended to silence me — the child — and more particularly, the girl child. Had I been a boy, they might have encouraged me to speak believing that I might be called to preach…Madness, not just physical abuse, was the punishment for too much talk if you were female.”

Blasting the charmed, privileged existences of white male canonical writers, she noted that their success was undoubtedly due to having unsung, unseen women partners cook, clean, and care for them and their children. By contrast, Black women writers could never be lone wolf artistic “geniuses” because of the constant demands made on their time by family, jobs, the church, and “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy”. hooks’ coinage of this term laid bare the intersections of structural oppression, trauma, and disenfranchisement that Black women routinely experience in public and private spaces. Her fierce commitment to truth-telling, no matter how ugly, painful, or in-your-face subversive of sacred cows like Black patriarchy was a gold standard for Gen X Black feminist writers. Coming to voice as survivors in the post civil rights movement era, we were told that allegiance to Black men, Black patriarchy, and Christian religious mores were more important for furthering the race than our own self-determination. Hooks’ tireless critiques of the ways sexism, misogynoir, and Black folks’ investment in patriarchy undermined Black liberation were foundational for our understanding of how these disparities played out in real life. Throughout her vast body of work, she amplified the ways Black women’s bodies were commodified for capitalist consumption, power, and control. She spoke bravely of her own victimization in a violent relationship, and the silence and shame she endured disrupting the narrative of the strong, indomitable Black woman in the midst of her trauma. Long before language acknowledging victim-blaming and shaming entered mainstream discourse with the #MeToo movement, hooks broke down how toxic myths of Black Jezebel hypersexuality and Black Mammy asexuality enabled the erasure of Black women’s specific experiences with domestic violence.

Hooks was part of a rich tradition of Black feminist and womanist writers who did this essential labor. She relished her mission as a prolific writer who insisted on Black women’s “birthright” of unfettered speech — big name publishers, ivy league universities, and celebrity influencers be damned. She championed liberating feminist education and praxis from the stranglehold of colleges and universities. Her call that “feminism is for everybody” was a powerful acknowledgment that K-12 youth of all genders needed feminist education to understand and combat the direct impact institutional racism, sexism, and heterosexism had on their lives.

Weaving personal narrative with critical theory and pop culture references, hooks always had the courage and audacity to challenge orthodoxies from all sides. In her 1992 essay “Revolutionary Black Women”, (from the landmark book Black Looks: Race and Representation) she cautioned against cults of personality that prevent younger Black women from learning from the examples of Black women freedom fighters like Angela Davis and Shirley Chisholm. For hooks, it was important that “Coming to power, to selfhood (not) happen in isolation. Black women need to study the writings, both critical and autobiographical, of those women who have…chosen to be radical subjects.” Hooks dubbed this “critical pedagogy” an essential part of Black feminist education, of coming to critical consciousness in hostile spaces and institutions where we “are assaulted daily”.

Ultimately, “Most Black women are ‘punished’ and ‘suffer’ when they make choices that go against the prevailing societal sense of what a Black woman should say and do…whether she has called herself a feminist or not, there is no radical Black woman who has not been forced to confront and challenge sexism. If, however that individual struggle is not connected to a larger feminist movement, then every Black woman finds herself reinventing strategies to cope when we should be leaving a legacy of feminist resistance that nourishes, sustains, and guides other Black women and men.” She also recognized the value of constructive critical engagement and redress, candidly calling out the harm that Black women do to each other under the guise of “sisterhood”. When differences among Black women are demeaned and devalued, the rich complexity of Black subjectivity is suppressed. As a Black feminist atheist and humanist, hooks’ commitment to truth-telling about the dangers of Black orthodoxy has resonated with me personally. Oftentimes, some of the staunchest guardians of religious morality and respectability, as well as gender norms, are Black women who self-identify as faith-based. Having one’s Black card “revoked” for being inauthentic and traitorous is practically pro forma. Hooks’ work has always provided a framework for challenging this form of policing.

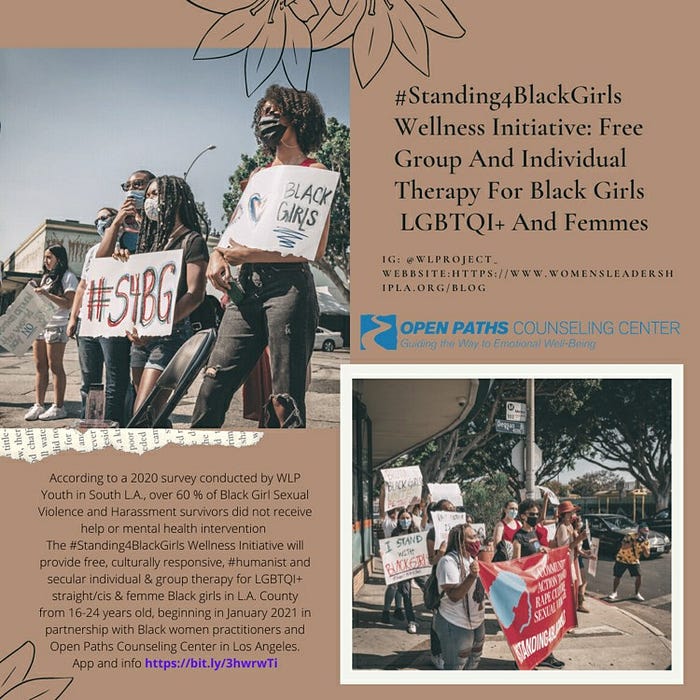

By identifying how communities of color internalize white supremacy, misogynoir, and homophobia, her entire body of work is essential to restorative and transformative justice. I’ve used hooks’ work to teach high school students to interrogate the toxic role normalized sexism, sexual violence, and harassment play in their lives. The young Black and Latinx women in the Women’s Leadership Project consistently express anger and anxiety about the devaluation of their experiences with sexism, rape culture, and victim-blaming, shaming and silencing. At the beginning of the year, most are only superficially aware of what distinguishes Black feminism from mainstream Eurocentric feminism. Fewer still are knowledgeable about the Black women pioneers who spearheaded Black liberation movements and how the issues that they fought for relate to their contemporary struggles. Yet, the seeds of anti-sexist resistance and critical consciousness are reflected in their inner voices — questioning male domination in their households, toxic masculinity in their everyday lives, and the double standards queer and straight girls experience when their sexuality is constantly policed at school, in the media, and in the community. As they move into Black feminist critical consciousness, they begin doing anti-racist peer education outreach and teaching in high school classrooms on reproductive justice, domestic and intimate partner violence, mental health, and LGBTQI+ youth empowerment. They also participate in the #Standing4BlackGirls rally and task force to develop mental health and educational resources for Black girl survivors.

In her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress, hooks writes that the “classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy.” Extending her global classroom to us through her radical imagination, hooks made this space possible for all the “yearning” Black girls who are reading, writing, speaking and blowing up the margins of silence, trauma, and invisibility.